The traditional Chinese liquor baijiu is said to be the most consumed spirit in the world, but only a small amount is found outside the country’s borders. While most view it as a single product, the broad range of grain-based liquors within the category can seem unrecognizable from one another, the result of centuries of differing traditions and geographical influence.

Unlike popular spirits like Scotch or Bourbon, there’s no official group that regulates baijiu. However, there are four main styles kept to by most producers. These are known as strong aroma, sauce aroma, light aroma, and rice aroma. The styles differ in grain, fermentation and distillation, and even within those classifications, brands showcase signature blending techniques.

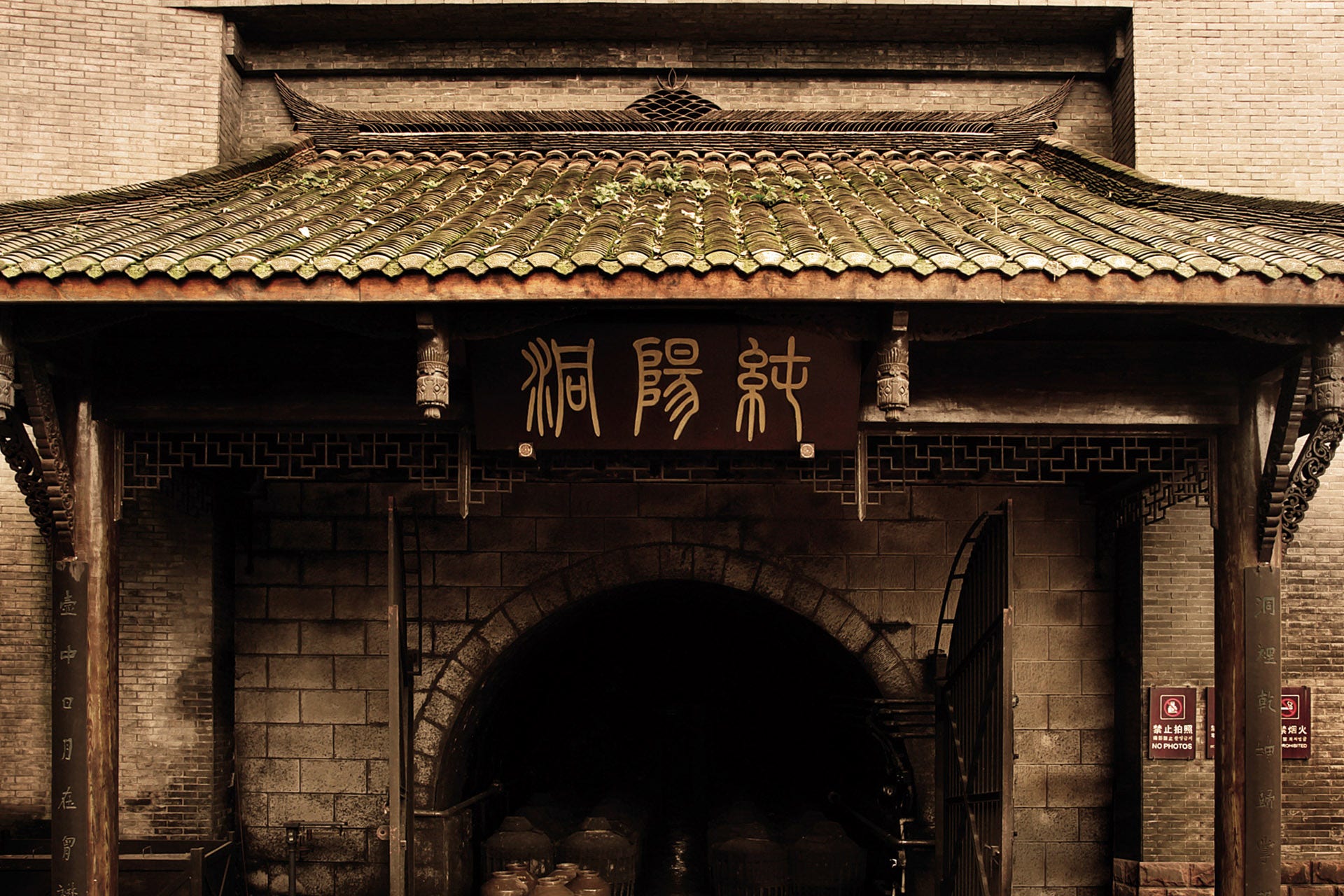

Baijiu adheres to traditional methods of production and distilling that have been preserved over centuries.

What is baijiu made from?

Baijiu is made from grain, usually sorghum or rice, with additions of sticky rice, wheat or corn being common. Grain husks are also used, though judiciously, as they can create undesirable flavors in large quantities.

Baijiu distillation is a long-preserved art that remains hands-on and labor intensive to this day.

The majority of baijiu is based from sorghum, and high-quality examples are usually made from local grains, like the red variety of sorghum used in Sichuan province. Less expensive versions rely on imported grain to meet demand.

Qu, one of the most important ingredients in China

Regardless of style, all baijiu is made with qu, a composite of yeast and mold cultivated with grains and formed into cakes or balls. Qu is a cornerstone of Chinese cuisine, used not only to produce rice wine and spirits, but also soy sauce, vinegar and bean paste.

Qu does much more than the average wine or beer yeast, and its role is vital to understanding what makes baijiu distinctive.

Spent distilled grain in strong aroma baijiu is constantly added back to the pit indefinitely, forming a mash of fermentation that can literally be centuries old.

Unlike a winemaker’s grape must, or the sugary, liquid wort distilled into whiskey, baijiu is derived from solid grain.

Qu contains microbes that simultaneously cause saccharification and fermentation. In other grain spirits, saccharification, the conversion of carbohydrates into fermentable sugar, is achieved separately from fermentation through malting or cooking the mash. Once the sugars have been converted, yeast is added. With baijiu, qu allows both processes to occur at the same time.

How baijiu is made

Baijiu distillation is a long-preserved art that remains hands-on and labor intensive to this day. Grain composition and qu are important, but so is the water used, as well as the age of fermentation and aging vessels.

Luzhou Laojiao, in Sichuan province, is one of the largest distilleries in China and among the oldest still in operation, founded in 1573. It produces strong aroma baijiu using regionally grown sorghum, utilizing a continuous pit fermentation method invented in the area in 1425.

Luzhou Laojiao currently operates 1,600 baijiu pits, more than a thousand of which are at least a century old. Because of this process, it’s difficult to ramp up production quickly to meet market whims.

Before there’s even a distillate to age, the qu imparts the grain with terroir and characteristics from the distillery itself.

Luzhou Laojiao’s process to create their strong aroma style starts in mud-lined pits. Previously distilled grain is mixed with fresh-steamed grain. It’s then inoculated with qu and fermented for 2–3 months. Other styles employ a stone-lined pit or clay jars instead of mud for this process.

When it’s ready to be distilled, the grain from the pit is loaded into a pot still in one-ton batches. These stills resemble the steamers you might find in a Chinese kitchen.

The mash starts at about 3.2% alcohol by volume (abv), while the resulting liquor registers at 60–67% abv, a level uncommon for a spirit undergoing single distillation in a traditional pot still. This occurs thanks to a cooler layer of grain and bran added to the top of the mash before distillation, which causes water to re-condense and sink back down into the mash, causing an effect not unlike a column still. After a batch is distilled, the spent grain is shoveled to the distillery floor to cool before it’s reinvigorated with more qu. It is then returned to the same pit it came from, individual layers separated by a sprinkling of husks.

The layers are valued differently. The oldest at the bottom are the most prized, while the top is often discarded. These details are taken to consideration when it’s time to blend.

Ming River, new to the U.S. market, sources its baijiu from Luzhou Laojiao and emphasizes the importance of the distillery on the final product.

“The longer a fermentation pit is used, the greater the complexity of the resulting spirit,” says Simon Dang, Ming River’s global director of marketing. “Luzhou’s fermentation pits are considered mature after being in continuous use for at least 30 years.” Luzhou Laojiao currently operates 1,600 baijiu pits, more than a thousand of which are at least a century old.

Because of this process, it’s difficult to ramp up production quickly to meet market whims. Aged baijiu is prized among connoisseurs, but a distillery’s output is limited by the readiness of its fermentation pits, which are continually evolving.

Baijiu is available at every price point, and most distilleries offer a range of bottlings. Some less-expensive offerings are blends of younger stock, while others are produced using liquid fermentation. Some budget bottlings are simply cut with neutral grain spirit. The exception is rice baijiu, which is made typically through a semi-liquid fermentation process.

How does baijiu taste?

Perhaps due to a lack of genuine exposure outside of its native country, baijiu has developed a reputation for being fiery and face-scrunchingly unpalatable. As with any high-proof spirit, the drink can be bracing, although many are bottled at 40% abv. Beyond the heat of alcohol, there’s a complexity of flavor that can stun the uninitiated.

Sauce aroma baijiu

Sauce aroma is the most pungent style of baijiu in regard to savory notes expressed. Among them is Moutai Prince, a widely available option from Kweichow Moutai. It’s a paragon of this style, with a nose of shitake mushroom and lingering roasty palate not familiar to most Western drinkers.

Sauce aroma differs from strong aroma baijiu in fermentation. Sauce aroma fermentation often occurs in stone-lined pits, rather than mud. Also, previously distilled grain is reused up to eight times when creating sauce aroma, before being discarded.

Strong and light aroma baijiu

In contrast to sauce aroma, spent distilled grain in strong aroma baijiu is constantly added back to the pit indefinitely, forming a mash of fermentation that can literally be centuries old.

The final product has a concentrated nose that may seem almost chemical in nature, but a deeper look yields a ripe nose evocative of yellow pineapple, green apple and sweet tropical fruits, but with a long, earthy finish.

Light aroma is named in its relation to strong aroma, retaining some of that same fruit character, though with less intensity. Many could be compared to a floral grappa. Kinmen Kaoliang, a popular brand in this style has a nose of chamomile with a slightly oxidative, savory finish.

Rice aroma baijiu

The mildest of the four styles is rice aroma. Rice baijiu, which originated in southeastern China, is fermented traditionally in jars. Steamed grains of rice are mixed with qu, and after the sugar is released, water is added to assist fermentation.

Vinn Distillery in Oregon produces this style from brown rice harvested in California, and even makes its own qu. The business began as a retirement project for Phan Ly, who had been making rice baijiu at home based on the methods used by his family in China and Vietnam over seven generations.

“All manner of business happens at the dinner table. You never talk about anything you need to talk about until the end. It‘s about toasting and if you don’t drink, you’re not trustworthy.” —Lillian Chou

Still a small operation, Vinn ferments in small brewer buckets and distills in pot stills. Ly’s daughter, Michelle, says the family is looking to expand their method.

“It’s hard to find clay pots that are specific to spirits, but we just found a local company, they’re maybe five miles away from us, [that] started making clay pots to age wine,” she says. “We’re really excited to have found them, and we’re going to start doing some batches this year…in a more traditional way.”

Michelle compares her family’s baijiu it to a mix of “sake with the rice aroma, and Tequila which is earthy from agave, and that botanical style that reminds me of gin.”

How to drink baijiu, and baijiu etiquette

“All manner of business happens at the dinner table,” says Beijing-based food writer Lillian Chou. “You never talk about anything you need to talk about until the end. It‘s about toasting and if you don’t drink, you’re not trustworthy. You have to toast your host, you have to toast your guest.”

At meals, baijiu is poured in thimble-sized glasses. When you toast, you’re expected to shoot it in one go, an action repeated throughout the night. Weddings are a prime example.

“You have to go and toast every table, and if you’ve got 10 tables, you’re supposed to drink 10 shots,” says Chou. “That’s [for a wedding with] 100 people. Imagine a 300-person wedding.”

Is it polite to refuse a toast? Not exactly.

“You can’t drink and stop,” says Chou, though a medical issue can excuse you from compulsory toast progression. However, it’s also impolite to drink until someone toasts you, so the tradition does ensure everyone at least stays on the same level.

Will baijiu ever be big outside of China?

The spirit’s unpalatable reputation is one of the biggest hurdles to bringing baijiu outside China. As a terroir-forward spirit, one would hope Westerners would find it as interesting as mezcal or Armagnac, but changing established tastes isn’t easy.

Ming River makes education vital to its campaign. That means teaching drinkers about all styles of of the spirit, not just their own brand.

Baijiu means many different things to the people who drink it. The word, which simply translates as “clear liquor,” is the same whether you’re talking about the home-distilled stash of a rural farmer or a pricey bottle gifted between associates. But as more receptive drinkers are introduced to baijiu, there’s an opportunity to better understand this complex historical drink.

Published: June 28, 2018